Emerging Perspectives on Hybrid Speciation in Nature

Written on

Chapter 1: Understanding Hybrid Speciation

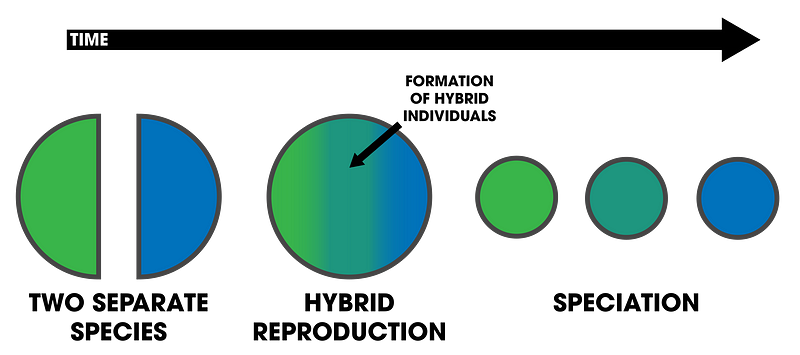

Contrary to popular belief, hybridization can occur naturally in the wild, resulting in the emergence of a new species. This revelation significantly impacts our comprehension of species evolution.

Salvin’s medium-billed prion (Pachyptila salvini) is a striking example, believed to be a hybrid of the Antarctic prion (Pachyptila desolata) and the broad-billed prion (Pachyptila vittata). This bird was observed in the Crozet Islands, a small archipelago located in the southern Indian Ocean.

Ligers! Tigons! And bears! Oh my!

Recently, I discussed a remarkable songbird that turned out to be a hybrid from three different species. This unique case raises the question: can hybrids give rise to a legitimate species?

While hybrid speciation is uncommon in the animal kingdom, it does occur under specific circumstances. In this process, a hybrid population becomes a new, independent species that is reproductively isolated from its parent species. For instance, the Heliconius butterfly is renowned for its stunning variety and mimicry, showcasing how hybrids can thrive in diverse environments.

Among birds, notable hybrid species include the Italian sparrow (Passer italiae), golden-crowned manakin (Lepidothrix vilasboasi), and a recently recognized Galapagos finch that emerged in the 1980s.

Despite these examples, the notion of a new species evolving through hybridization challenges Darwinian principles since it contradicts the core definition of a species: reproductive isolation. Furthermore, because each species is adapted to its unique ecological niche, hybrids often exhibit intermediate traits that may not be well-suited for survival, leading to their decline over time. Thus, hybrid speciation remains a largely unexplored concept in animal biology.

However, in rare instances where a hybrid species is better adapted to a specific niche than its parent species, it can potentially replace one or both of them or occupy a new ecological niche entirely.

Genetic limitations do exist that hinder hybrid speciation in animals. The most persistent hybrid species possess the same chromosome count as their parent species, indicating that closely related species are essential to avoid genetic anomalies. This type of hybridization, termed homoploid hybrid speciation, is prevalent among animals. A classic example is the mule, a hybrid of a horse and a donkey, which are genetically incompatible due to differing chromosome numbers, resulting in sterile offspring.

Chapter 2: Investigating the Prion Species

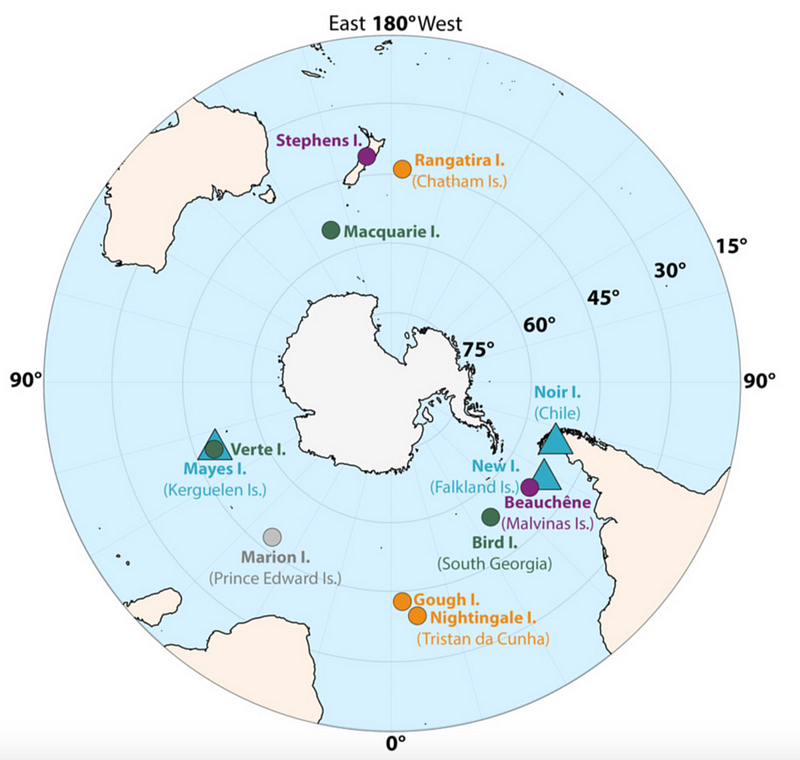

Dr. Juan Masello, a Principal Investigator specializing in the ecology of birds, along with his team, delved into the relationships among prions, a group of closely related seabirds.

Pachyptila prions, characterized by their pigeon-like size and distinctive coloration, are predominantly found in the Southern Ocean. These seabirds are remarkably similar, particularly in flight, navigating the turbulent waters of sub-Antarctic regions.

Dr. Masello and his colleagues aimed to clarify how many Pachyptila species exist. Initial phylogenetic studies suggested between two to seven species, but this was met with some controversy.

As the team continued their research, they observed unexpected traits in Salvin’s medium-billed prion (Pachyptila salvini). Their analysis revealed that this hybrid species breeds exclusively on Marion Island, establishing genetic separation from both parental species.

Their findings also indicated that prions could be identified not only by their breeding locations but also by their distinctive bill shapes, crucial for foraging efficiency.

Upon measuring the bill dimensions across six Pachyptila species, they noted that there was no overlap in measurements, further supporting the uniqueness of each species.

Dr. Masello's team sequenced DNA from 425 individuals across five Pachyptila species and the closely-related blue petrel (Halobaena caerulea). The mitochondrial DNA linked Salvin’s medium-billed prion to the Antarctic prion, while nuclear DNA analysis suggested a connection to either the Antarctic or broad-billed prion, hinting at a hybrid origin.

The most surprising outcome of their research was the realization that the combination of traits from both parents not only enhanced fitness for Salvin’s medium-billed prion but also led to its reproductive isolation.

This study illustrates that hybridization does not necessarily signify the end of evolutionary progress; rather, it can be a pathway to the formation of new species.

The findings prompt a reevaluation of the frequency of hybrid speciation, particularly in rapidly evolving species groups where reproductive isolation is still developing.

Source:

Juan F. Masello, Petra Quillfeldt, Edson Sandoval-Castellanos, Rachael Alderman, Luciano Calderón, Yves Cherel, Theresa L. Cole, Richard J. Cuthbert, Manuel Marin, Melanie Massaro, Joan Navarro, Richard A. Phillips, Peter G. Ryan, Lara D. Shepherd, Cristián G. Suazo, Henri Weimerskirch, and Yoshan Moodley (2019). Additive Traits Lead to Feeding Advantage and Reproductive Isolation, Promoting Homoploid Hybrid Speciation, Molecular Biology and Evolution, msz090 | doi: 10.1093/molbev/msz090

Originally published at Forbes on 23 June 2019.