The Future of Florida's Manatees: A Delicate Balance with Power Plants

Written on

Chapter 1: A New Perspective on Manatee Habitats

The Big Bend Power Station, a sprawling 1,500-acre facility established in the 1960s for coal-generated electricity, presents a striking contrast. Solar panels line its parking area, hinting at a brighter future, even though they contribute minimally to the energy mix. During my visit, I found the temperature pleasantly cool at 53°F, ideal for witnessing a remarkable phenomenon. Stanley Kroh, who oversees land and stewardship programs for Tampa Electric Co., welcomed me at the Manatee Viewing Center, where the sounds of an enthusiastic greeting echoed.

Kroh expressed the common misconception he encounters: “People often ask, ‘Isn’t it unfortunate that a power plant is right next to a manatee sanctuary?’ They misunderstand the situation entirely.” We walked along a cement path shaded by mangroves, leading to a narrow pier extending into a wide canal. Nearby, towering piles of coal loomed, and conveyor belts transported it to the plant's generation units, which also utilize natural gas and draw cooling water from Tampa Bay.

Amid the murky waters stirred by leaf tannins and warmed by the constant flow of heated water, a hundred or more manatees floated, their forms obscured until they surfaced for air, releasing a spray and a pronounced puff of breath.

Manatees are often likened to gentle giants of the sea, their herbivorous diet consisting primarily of seagrass. These creatures, while vulnerable, have managed to thrive despite numerous threats, showcasing a remarkable evolutionary resilience. Despite their large size, they evade predation, existing in a delicate balance within their ecosystems.

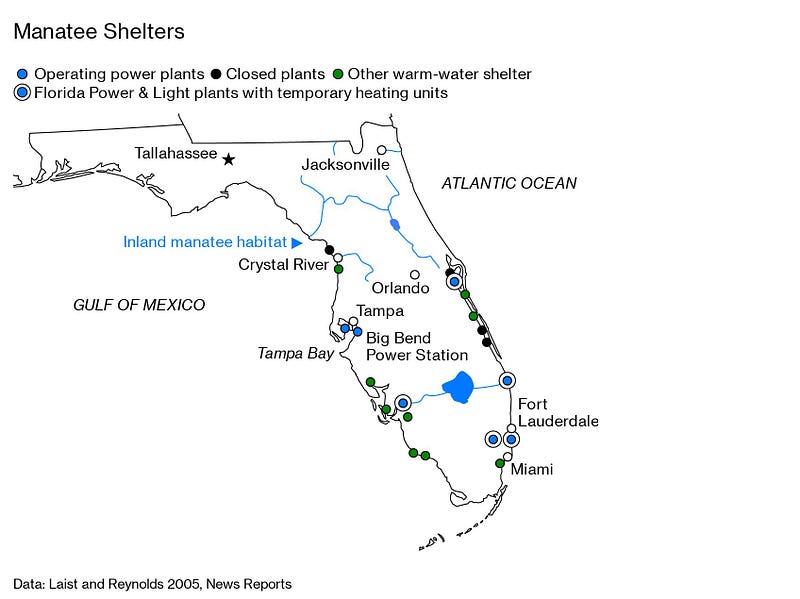

While manatees faced near extinction due to hunting in the 19th century, conservation efforts, including a hunting ban and their designation as an endangered species, have contributed to their population recovery. However, an unexpected twist in their resurgence involves a network of for-profit power plants. As their natural warm-water habitats dwindled, manatees began seeking refuge in the outflows of coal and oil-fired plants. Approximately half of Florida's estimated 7,500 to 10,300 manatees now rely on these thermal discharges for survival.

This illustrates Kroh's point: the power plant did not encroach upon the sanctuary; rather, the manatees migrated here, traveling over 100 miles north of their natural habitat to seek warmth in the canal's heated waters. TECO Energy Inc., which operates Tampa Electric, has embraced this unexpected bond, promoting manatee viewing as part of their public relations strategy while being one of Florida's major polluters. As a result, manatees have become cherished symbols of the state, drawing significant tourist interest.

However, a troubling scenario looms as these aging power plants transition from coal to natural gas and renewable energy sources. This shift, while beneficial for reducing emissions, may inadvertently leave thousands of manatees without their vital warm-water sanctuary. Four of the ten plants that historically supported these animals have already shut down, and Big Bend is set to retire one of its coal-fired units soon.

The first video titled "Why Do Manatees Die When Power Plants Shut Down?" explores the critical relationship between manatees and these energy facilities, highlighting the risks posed by the plants' closures.

Chapter 2: The Uncertain Future for Manatees

As power plants undergo significant upgrades, the challenges for manatees intensify. Research indicates that these animals may struggle to adapt to the loss of artificial warmth. Temporary measures, such as artificial heaters, have been attempted but prove impractical, particularly at Big Bend, where the canal's vast size complicates heating efforts.

In the winter of 1949, biologist Joseph Curtis Moore first documented the relationship between manatees and power plants, observing their attraction to the warm discharges. As Florida’s human population surged and natural habitats were destroyed, manatees increasingly relied on these thermal refuges.

The Clean Water Act of 1972 introduced restrictions on thermal pollution, threatening the very survival of the manatees that had come to depend on the plants for warmth. Efforts to balance the needs of manatees with the operational requirements of power plants led to a compromise: allowing continued warm-water discharges, crucial for manatees but potentially damaging to other aquatic life.

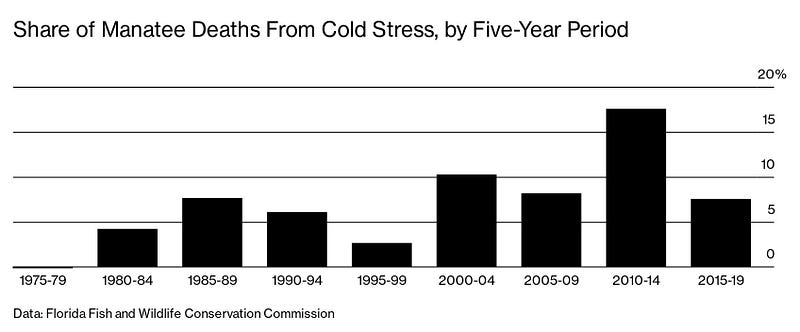

Despite the manatees' increased numbers, concerns about their long-term viability persist. The 2010 cold snap resulted in a massive die-off, with 480 manatees lost due to cold stress. This tragedy underscored the precarious nature of their reliance on power plants for survival.

The second video titled "Manatees gather around Florida power plant to stay warm" showcases the phenomenon of manatees flocking to power plants during colder months, illustrating their dependency on these artificial habitats.

As Florida navigates this delicate balance between energy needs and wildlife conservation, the future of manatees hangs in the balance. The challenge remains: finding sustainable solutions that ensure the survival of these gentle giants amid the evolving landscape of energy production.

In summary, the complex relationship between Florida's manatees and power plants highlights the urgent need for thoughtful conservation strategies. As we face the realities of climate change and habitat loss, it is crucial to prioritize the future of these vulnerable creatures and their ecosystems.