Title: Exploring the 1889 “Russian Flu”: A Historical Reflection on Pandemics

Written on

Chapter 1: The Illustrious Prince Eddy

In the year before his untimely demise, Prince Albert Victor, affectionately known as Prince Eddy, was a striking young man and the grandson of Queen Victoria. At just 28 years old in 1892, he stood second in line for the British throne, freshly engaged and celebrating the New Year with a shooting party. However, just two weeks later, he succumbed to pneumonia.

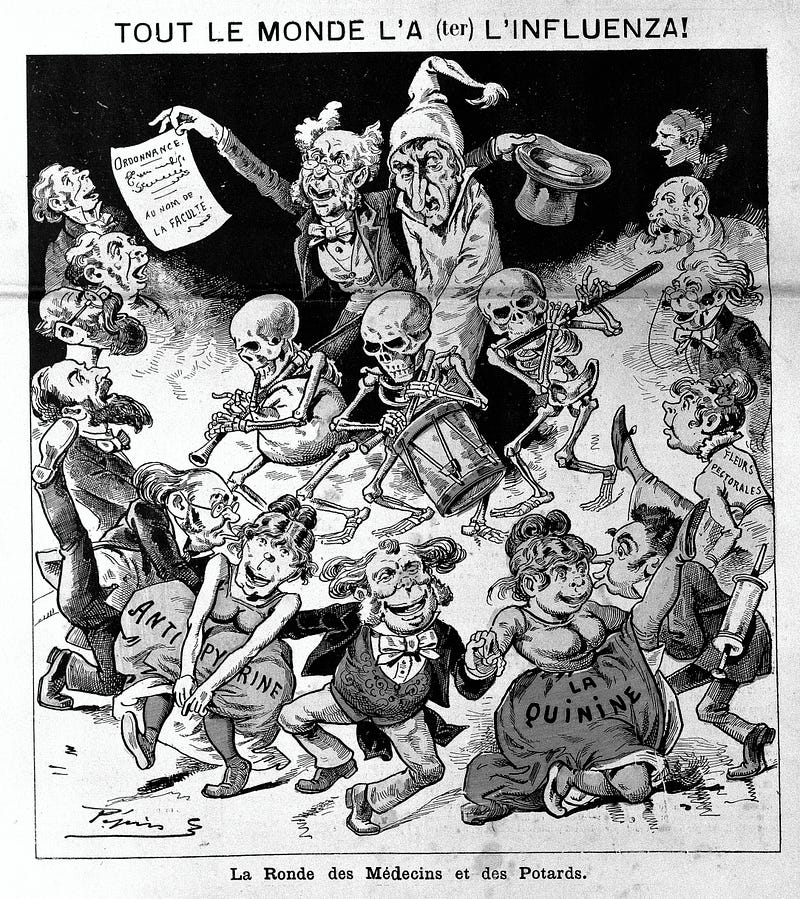

Eddy's passing was among the many attributed to the “Russian Flu,” a pandemic that emerged in 1889 and subsequently swept across the globe, returning in seasonal waves over the following years. This illness was characterized by high fevers and severe lung inflammation. Some individuals reported losing their sense of taste and smell, while others experienced widespread symptoms affecting various bodily systems. Many suffered from lingering effects, struggling to regain normalcy for months or even years. Intriguingly, the virus seemed to impact older individuals more than younger ones, with children, typically the most susceptible demographic, largely unaffected.

Sound familiar?

There might be a reason for that. Some researchers speculate that the “Russian Flu” may not have been influenza at all but rather a coronavirus akin to the one that has caused extensive suffering in recent years. The trajectory of the 1889 pandemic could provide insights into our current situation.

To clarify, the theory suggesting that the Russian Flu was a coronavirus remains unverified, and we may never fully understand the pathogen responsible for the outbreak. The 1889 pandemic holds a peculiar position in the history of human disease interaction. By this time, medical science and communication technologies had evolved enough to allow for real-time tracking of the pandemic across the globe.

We know its origins (Siberia, May 1889) and its spread (through Eastern Europe, reaching North America by January 1890, and even remote New Zealand by May 1890). At that point, medical professionals had a basic understanding of disease transmission; the belief that illnesses stemmed from “bad air” was fading. The pandemic may have claimed up to a million lives from a population of 1.5 billion.

However, we will likely never definitively identify or analyze the pathogen that triggered this outbreak. Those who lived through it lacked the knowledge that would later assist scientists; the concept of “viruses” was only recognized in 1892, and it wasn't until the 1930s, with the advent of the electron microscope, that viruses were visually observed. No samples of the pathogen were preserved, as no one thought to collect them.

Chapter 2: Echoes of the Past

The similarities between the current coronavirus pandemic and the events of 1889 are striking. The virus from 1889, like our present adversary, proved deadly, yet it did not galvanize society into a unified effort to combat it. Many victims suffered from pre-existing health conditions that rendered them more susceptible to pneumonia, complicating the attribution of their deaths. Official mortality rates varied, and many dismissed the illness, continuing with their daily lives. The New York Evening World famously remarked, “It is not deadly, not even necessarily dangerous, but it will afford a grand opportunity for the dealers to work off their surplus of bandanas.”

Contrarily, firsthand accounts from doctors, who witnessed the worst of the illness, painted a more severe picture. One British physician described the symptoms as follows:

“The onset is abrupt; accompanied by intense back pain, often with dizziness and nausea, and sometimes actual vomiting. Patients experience generalized aches, severe frontal headaches, eye pain exacerbated by movement, shivering, an overwhelming sense of misery, weakness, and great emotional distress, along with restlessness, insomnia, and occasionally delirium. Some exhibit respiratory symptoms… with red eyes, sneezing, sore throat, and even bleeding from the throat. A harsh, dry cough, particularly severe at night, is common. Tenderness of the spleen is often present, with a temperature ranging from 100°F in mild cases to 105°F in severe cases.”

Beyond symptom similarities, additional evidence suggests that the 1889 pandemic may have been caused by a coronavirus. Prior to the emergence of COVID-19, Belgian researchers indicated through genetic analysis that coronavirus OC43, responsible for some common colds today, diverged from bovine coronaviruses around the time of the 1889 outbreak.

If the 1889 pandemic indeed stemmed from a zoonotic coronavirus, its trajectory might illuminate our future. The Russian Flu caused widespread devastation globally for years before it either mutated or human immune systems adapted. It’s conceivable that the virus responsible for the deaths of a million people in the late 19th century has now evolved to merely cause mild colds.

Most experts predict that COVID will become endemic, with many believing it will lead to less severe illness as immunity increases among the population and the virus continues to adapt. It is possible—though certainly not guaranteed—that in decades to come, the virus that currently causes COVID will be associated with minor ailments, and the devastation it wrought will fade into memory, much like the 1889 pandemic.