The Disturbing Legacy of Brainwashing and Media Manipulation

Written on

Chapter 1: The Alarm of Brainwashing

In the early 1950s, fears of communism gripped the public. Edward Hunter's provocative book, Brain-Washing in Red China, published in 1951, set off a frenzy. After extensive research, he claimed to uncover the “frightening techniques that have mesmerized an entire nation.” Interestingly, the term "brainwashing" derived from the Chinese term xinao (洗脑), which means “to wash the brain,” a concept rooted in Buddhist and Taoist philosophies concerning mental clarity. Hunter overlooked the deeper cultural significance of the term, becoming increasingly convinced that he had stumbled upon the secret to communism's success.

Following the book's release, over two hundred publications produced articles on alleged communist mind control. TIME Magazine even weighed in, asserting that brainwashing was a dominant force in Red China. However, when TIME credited its Hong Kong correspondent without mentioning Hunter, he questioned their editorial integrity. Later, during congressional testimony, he insisted, “I was the first to write the word [brainwashing] in any language.”

Edward Hunter, the man who popularized the term, seemed more focused on fame than journalistic ethics. The issue resurfaced after the Korean War when twenty-one American POWs opted not to return home, fueling fears of communist indoctrination. The military later reported that no verified cases of actual brainwashing had been found among American POWs. Despite the lack of evidence, fascination with the concept only grew, creating a media frenzy around the notion of manipulating human thought.

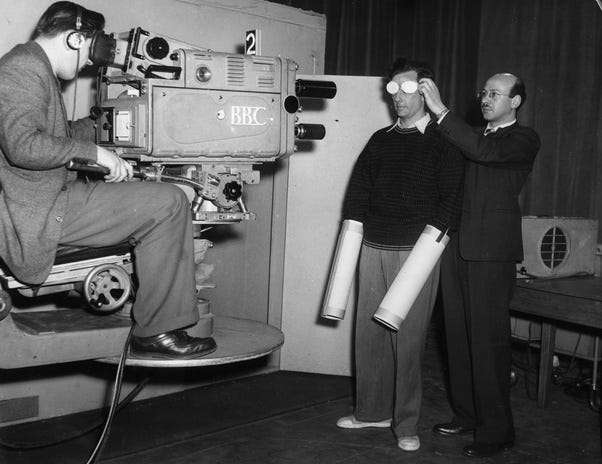

The CIA, recognizing the ensuing panic, sought to counteract perceived communist threats. They established covert prisons abroad, where harsh torture was paired with mind-altering substances. Many suffered grave consequences, yet the elusive formula for creating mind-controlled agents was never discovered.

After President Gerald Ford enacted an executive order banning human experimentation without informed consent, John D. Marks pursued a Freedom of Information Act request against the CIA. His findings revealed that neither the Chinese nor the Russians significantly employed drugs or hypnosis in their methods, which were largely based on ancient practices.

The Truth Behind "Brainwashed" Soldiers

The Western obsession with brainwashing raises compelling questions. Scholars Sarah Marks and Daniel Pick from the University of London argue that this fixation allowed Americans to avoid confronting the uncomfortable reality of why individuals might willingly choose communism. Delving into the facts could lead to unsettling truths, making the narrative of brainwashing an appealing alternative.

Few considered that the American soldiers' choice to remain abroad might stem from genuine reasons. Clarence Adams, an African American soldier, had experienced deep-rooted poverty and racial discrimination before joining the army. “Our mission was to liberate South Korea,” he reflected in his autobiography. However, he soon realized that the American military was indifferent to social justice, leading him to question the purpose of his fight.

The turning point came when the 503rd Field Artillery was ordered to hold its position while others retreated, leaving them vulnerable. After facing dire conditions and witnessing comrades perish, everything changed under Chinese administration in the camp. Unlike their previous experiences, prisoners were treated with basic dignity, receiving food and clothing. They were also introduced to the communist ideology of equality.

“Unlike anything I had known,” Adams recounted, “I felt treated as an equal.” The camp fostered an environment of education, where prisoners could learn to read and attend lectures from university professors. Initially attending out of politeness, Adams became captivated by the Chinese perspective, which starkly contrasted with his experiences in America.

As the war neared its end, Adams dreaded returning to a society marred by segregation and discrimination. He even expressed interest in relocating to China post-war, convinced that the reality he faced in America was bleak compared to the possibilities he experienced in the camp.

When American media reported on the soldiers who refused repatriation, the narrative of communist mind control took center stage. Some articles suggested that the Chinese specifically targeted Black soldiers for brainwashing. “Brainwashed?” Adams later remarked, “The Chinese helped me see beyond the false narratives I had been fed.”

American society avoided grappling with the notion that these soldiers might have acted of their own volition, preferring instead to paint them as unwitting victims of communist deception. Acknowledging their agency would require confronting uncomfortable truths about the state of America itself.

William Worthy, a journalist for the Baltimore Afro-American, was one of the few to provide an honest appraisal of the situation. He noted that while many Black soldiers did not develop fondness for their captors, most returned home disillusioned. “The United States lost the war in Korea, make no mistake about it,” he wrote.

Explore the history of brainwashing from Pavlov to social media.

Chapter 2: The Compelling Narrative of Mind Control

The narratives surrounding brainwashing have transcended their origins, evolving into a tool for media sensationalism. The story of Clarence Adams exemplifies how misunderstood experiences can lead to misleading conclusions. As more accounts emerged, the media perpetuated the idea of brainwashing while neglecting the complexities of the soldiers' choices.

A documentary exploring the personal impacts of brainwashing on families.